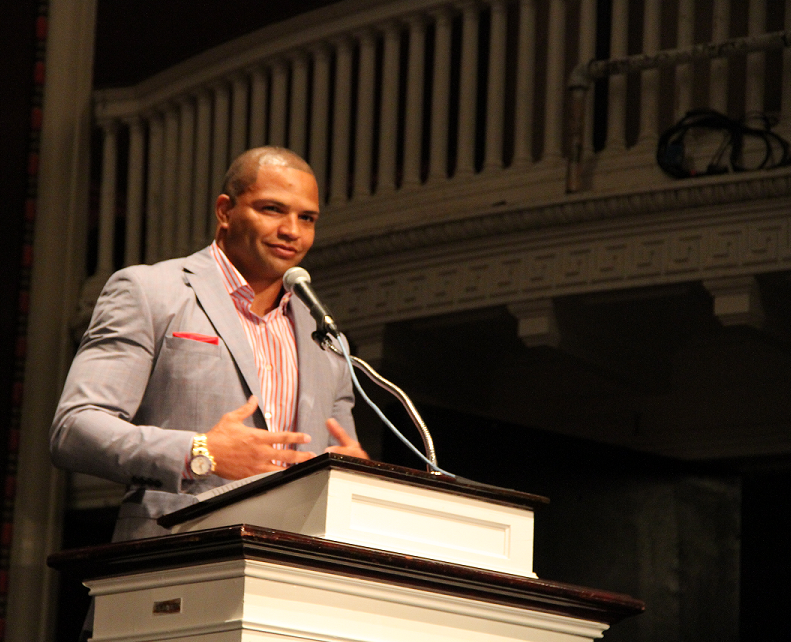

The secretary just smiled at me as I told her I was the POTUS’ 9 a.m. appointment, and went to go fetch him. I heard a door open and close, and pulled my notebook out of my bag as I saw her walk back out with President Casey in tow. I stepped around her desk; he smiled warmly and shook my hand, motioning for me to follow him back into the inner sanctum: the Oval office of McDaniel College (which isn’t an oval in any way). It’s actually rectangular and decorated according to how one might imagine– with a signed photo of Stephen Colbert framed and hanging on the wall. President Casey closed the door behind us as he offered me one of the plush winged chairs situated in the corner of the room across from his desk. The windows that looked out on to the Presidents balcony gave the room a lot of light, creating a well-lit and elegant atmosphere. The POTC (President of the Campus) sat down with his mug of coffee in hand and patiently waited for me to begin. I began the interview: “But yeah do you want to just start off; you’re early life, where were you born?”

POTC: “I was born… I grew up, in South Carolina. I grew up in a very, very small town in the upstate, and an only child.”

Forged in Car Parts and the Leaves of Books: “If people needed you, you went.”

In the age before zoning (the year 1961 to be exact) where junkyards were allowed to be behind someone’s private house, Roger Casey was born. The only child of a mechanic and a loving mother, Casey grew up in the small town of Woodruff, South Carolina. Playing on run down cars and spare parts that were located behind his house, each became a spaceship or a fort, fostering his imagination and instilling a sense of curiosity and adventure at a young age.

Woodruff, built around the textile and cotton industry, had completely lost vitality. The damage caused by the Reconstruction after the Civil War, mixed with the more recent destruction produced by the Great Depression in the late 1930s, had left the town barren of industry and employment, with little to no jobs left for those living there. The little employment opportunity available to the community was nothing new to the town. It was the same old story for most areas in the South; luckily Casey’s father’s automobile mechanic shop helped keep his family from feeling the affects of the community’s poverty.

His father’s automobile mechanic shop which was to be found right behind Casey’s childhood home, served as a place of instruction for the young President to be. Working on cars kept Casey busy, and it kept him curious. The phone in the house was constantly ringing with people who needed their cars fixed, and so he inherited his fathers need to fix things, “if people needed you, you went.” If anyone had asked at the time what “Casey’s kid” was going to do, they would have said he would be a mechanic, just like his father.

But this was not to be the case. Even though his parents didn’t really read to him, his “insatiable” curiosity led him to read “voraciously” regardless. He read anything he could get his hands on, including a 1950s set of Encyclopedia Britannica that his great grandmother had been allowed to take from the one room schoolhouse, located next to her log cabin (neither of which had electricity or running water). He became “obsessed” with trivia, especially after having read the encyclopedias; he had little tidbits of information running around his skull, bursting forth in what one can only imagine were epigamic moments of intellect and knowledge.

While Casey may have been too young to remember the strife of the Civil Rights battles of the 1960s (being only in the second grade when Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated) his middle and high school years were during a transformative era in the Southern society. While Woodruff was surrounded by a multitude of towns that were torn up by the adverse affects of segregation and later integration, the town suffered very little in comparison. Close to being 50 percent black and 50 percent white at the time, it was not a battlefield like other places; and when integration was put into affect, Casey was sent to the all black school where he received the best education he could have possibly been given.

POTC: “When integration happened, I wasn’t bused because the town was too small… I was essentially forced to go to what had been the all black school… but at that time the economic opportunities that were available to African Americans in that part of the south, if you were very smart, if you were very successful, if you were black… really one of the only opportunities available to you was teaching. So that school was filled with phenomenal teachers… and really probably because I was forced to go to that school, I probably had a much better opportunity and much better chance in my education opportunities… And I think that’s true of many white Southerners. That’s really a story of integration that’s just not told… when you talk about the history of what happened in the South.”

To be fair, President Casey attributes much of the collective harmony of the community to the Wolverines, the high school’s local football team. Football brought the town together, both across racial lines and economic/class lines. Everything had to do with the Wolverines; the town was a high school football powerhouse.

POTC: “[Woodruff] used football to bring [the] town together when many towns around us were in fights and had terrible race relations. Football really brought [Woodruff] together… you still go to this town… everything has to do with the Wolverines… the Wolverine house, the Wolverine shack. And when I was in high school we never lost a football game, we won the state championship every year.”

This sounded to me like a real life version of “Friday Night Lights.” The town came together around football and in having pride for their high school football team.

The College Years: “I’m pretty sure people don’t major in subjects in college, they major in people.”

I adjusted myself in the comfortable winged chair while President Casey’s coffee rested on his lap, held secure by one of his hands: he had hardly touched it as he dove into his college years.

It’s now the 1970s and the POTC’s early twenties. Accepted to Furman University in South Carolina, a driven and fiercely curious pre-med student (because all first generation college students are pressured by their families to enter into what might become a financially secure profession), Casey became obsessed with literature and decided to switch his major to English.

He joined the “College Quiz Bowl” team and soon became the Captain; the years he spent reading the set of 1950’s Encyclopedia Britannica’s late at night finally paid off. “The College Quiz Bowl” was a show about college teams competing on their trivia knowledge. It aired on U.S. television from the 1959 to 1970, with a seven-year hiatus until its revamp in 1977. The tournaments lasted for 31 years up until 2008 when the “College Bowl” Company announced its suspension of the program, citing costs and financing as the reason for termination.

In 1982, our President received a scholarship that gave him the opportunity to travel to London, England to study at London University and the Royal Shakespeare Company. He had never been on a plane before or left the country; going to London changed his life. Sitting in the chair across from him I imagined him sitting on a plane by himself for the first time, lightly gripping the armrests as the plane took off, feeling slightly anxious as it touched down in a country completely unknown to him, with no friends or family to facilitate the experience. He stepped off the plane in Heathrow, city-bound; how excited and nervous he must have been to meet and impress his temporary professors. I was reminded of my own experience studying abroad at McDaniel Budapest, and the nervous anticipation I faced as I took off and landed in a country where the language was not my own.

London made him fall in love with theatre; seeing a play every night and writing a review on each regarding the text, or the technical elements of the play due the following day gave him a singular appreciation for the art of acting. At the end of his three months he had seen a total of 90 plays and written an unimaginable number of pages on British theatre.

It opened his eyes to the world around him, to different human experiences, specifically the experiences of the Irish and their fight for independence, and Europe’s fight with Soviet Communism. Things were coming unglued from how they had been the previous century.

POTC: “The Irish troubles were pretty big in England. I remember when I was there all the trashcans disappeared over night… of course they got rid of them all because the IRA was putting bombs in all of them. So it was a really sort of interesting time to live there.”

Upon his return to the United States, President Casey graduated from Furman with an English degree and an appreciation for the Theatre Arts; both of these passions drove him to his graduate studies at Florida State University. Casey spent his time in Tallahassee working to obtain his master’s and doctorate in English, and performing in and directing shows put on by local community theatre groups. Now the big stuff was happening: he had his degrees, he had his education, now what to do with them?

A Real Job and a Real World: “My thesis was: how can you dramatically change an organization and keep all its people.”

POTC: “I went from college, and grad school, to real-time work.”

His first faculty appointment was at Burmingham Southern College, a Methodist institution very similar to McDaniel College (i.e. liberal arts, small, and community-driven) where he became extremely involved in leadership education.

He was chosen to be a member of the Kellogg Foundation, an organization dedicated to closing racial gaps, reducing vulnerability from poverty, and the advancement of child education within the United States and around the world. With the Foundation, he travelled to 20 countries within the span of three years. His thesis: “How can you dramatically change an organization and keep all its people?”

He visited the Dalai Lama’s compound in India, visited Buddhist monks in Thailand, and visited a New Age community in Northern Scotland, a group of sane people who had gathered around one woman who said God spoke to her through her peas. He spent time with Brujas in Guatemala and Chiapas; he was there during the Sandinista rebellion and really got a different view of what the rebels were trying to accomplish, a viewpoint that he found was not represented in the United States media.

And from 2000 to 2010, he was the Dean and Provost at Rollins College in Winter Park, Fla. In 2010 a search firm called him up and told him about McDaniel. That same year, he came to McDaniel College to serve as our college’s President.

The Age of McSwagger: “Cocky, is when you think you have the shit. Swagger is when you do have it.”

Now is the time for my questions pertaining to the campus and Dr. Casey’s life here at McDaniel: his reasons for changing the motto to McDaniel Swagger, his aspirations for the college, his obsession with pop culture, and his apparently splendiferous art collection.

I decided to start with pop culture, his obsession and his wonderful use of it in his speeches.

Me: “What is your favorite pop culture reference, whether it be a movie or perhaps music?”

The President smiled.

POTC: “That’s hard to talk about. When I was younger, television was the only escape I had from the world. Only when I got to grad school did I realize I actually had an academic skill. When I was in college nobody did critical pop culture stuff, I mean I might have been laughed out of the room if I had suggested to my professor ‘I’m going to write a critical perspective on television.’”

In 2003 to 2004, President Casey became really involved in studying hip-hop narratives, the story these artists had to tell, and the structure of hip hop.

POTC: “Some of these guys have something interesting to say…The type of place Eminem grew up: just outside of Detroit. The type of place I grew up, the trailer park life, the experience of who your friends are. The crossing cultures, the aspect of when a majority of your friends are from a different culture and you go kind of through cultural appropriation. This was my experience a lot during the 70’s too. Because many of the people I hung out with were African American, I really was into for lack of a better word their music, and that’s not necessarily what I was supposed to be listening to… Funk. And here’s Eminem, this white kid, who gets interested in rap music and I thought: so how does he wind up being him and I wind up being me?”

As I sat there listening to the President I realized that what he was doing with hip hop and pop culture was what those of us who listen to it every day try to do — connect with the artist and understand their suffering or their life experiences, and apply it to the liberal arts.

POTC: “I’m gonna try dropping these lyrics in a huge public forum, ‘cause either one of two things is going to happen: either it’s going to be huge comedy and I’m gonna look like an idiot or people will remember it.”

Working as Dean and then Provost at Rollins College, with no clue as to what would happen, he stuck on some sunglasses and threw down some Eminem lyrics and the group of students he was speaking to went crazy. After his first test run he received a call from a college that asked him to address an entire group of students.

And this year he’s found another fountain of material in Macklemore and Ryan Lewis. I mean, if you remember from “Choices,” he came out dressed like Macklemore from the music video “Thrift Shop” and dropped down his own “sick” lyrics to the song.

But listening to hip-hop and making students happy about the fact that they aren’t listening to another boring commencement speech isn’t the only thing that President Casey has been changing. So I decided to ask him about “McDaniel Swagger” or “McSwagger,” if you will.

POTC: “I was struck by two things when I first came to the college in 2010. The first one was the kind of underdog mentality that a lot of people had when they talked about McDaniel… the other thing had to do with just talking to football players… so I grew up in this town in which we never lost a football game… I go and get my graduate degree at Florida State and they win two national state championships in football and I’d seen the power that sports had in making people feel proud of an institution.”

He found that whenever he spoke to students or even faculty who worked at McDaniel, they spoke with an air of “oh we’re JUST McDaniel,” in other words this real lack of pride in the institution and he wanted to change that. He found too, that the Florida state team had this “swagger” about them, and he wanted that for McDaniel. He wanted the students and faculty who went to McDaniel to feel pride in their school, and in what they were doing.

He noticed that the various national rankings McDaniel had earned weren’t seen as a big deal, and he really wanted to make those come to the forefront of McDaniel’s image. He felt like McDaniel was hiding its grandeur, “under a bushel somewhere.” And in talking to some members of the football team, the term McSwagger was born.

POTC: “And then somebody said… ‘we got more than swagger, we got McSwagger and then McSwag took off.”

Of course, the POTC didn’t just use a new hip term without looking it up, and so off to the ultimate record keeper of “hip” terms he went — Urban Dictionary. And what he found finalized its definite use as a motto.

POTC: “ ‘Cocky is when you think you have the shit. Swagger is when you do have it’… this ties in to the whole attitude of… pride and… being a homey, I mean being somebody who represents a place”

The POTC came to McDaniel and wanted to create a school where the students could stand up proudly and declare that their school was just as important, just as culturally relevant, just as prestigious as big name schools like Cornell, Harvard, and Yale.

Amateur Art Collector: “Dirt Road and Dixie.”

As soon as my eyes skimmed my Word document, I spotted the perfect topic for a question: Art.

Me: “Apparently you have an art collection?”

POTC: “Yes,” he said with the affectionate smile of attachment. “When we lived in Alabama I got very interested in folk-art… it was becoming really internationally known at that point in time. And I got a fellowship with Alabama Humanities foundation to go around the state and meet various artists… who were known worldwide. Our job was to tell their stories.”

Me: “Is there a focus?”

POTC: “It’s all over the place, we’ve got folk-art and then one of our prized pieces is a Willem de Kooning piece.”

I bravely delved into his Howard Finster collection. My notebook was in hand as I asked him how on earth he heard about where to buy these pieces of art.

POTC: “I knew him. One of the artists that we studied and talked about. We would take people to meet Howard… I had a phenomenal class that I taught… called ‘Dirt Roads and Dixie’ and [we] would meet twice a week. Meet and talk about some aspect of Southern culture, some literature or something: Flannery O’Connor, Faulkner… and then Friday afternoon, we’d go meet someone that was a real life embodiment of whatever it was we’d been studying.”

We got quiet for a little bit as I took down a few words and let him think to see if he wanted to add anything else, and luckily a wonderful piece of advice I’d received a few weeks earlier of shutting up and letting the interviewee speak worked. He gave me this little gem.

POTC: “What I got really fascinated by was, these people…other people might call them crazy; people get a vision. What’s the difference between them and… one day Bill Gates wakes up and goes ‘God I think I figured this thing out’ or Steve Jobs goes, you know, ‘if you just carry this little thing in your hand that would move things on the screen,’ what’s the difference between that and Howard Finster going ‘God spoke to me through my little finger’?”

I didn’t really know what to say after that little thought was dropped on me, and while I know this might sound like sucking up, the man had me impressed.

Personal Time: “I wouldn’t mind having a kid born at the age of 18 with a full college scholarship… I like 18 to 22.”

After the answer to my art question, I only had a few things left to ask and the first one was if he had any kids, and he responded very simply with a “no,” but made sure to point out he had a lot of quasi kids from all of the schools that they (he and his wife) had worked at and therefore had essentially adopted.

POTC: “I wouldn’t mind having a kid born at the age of 18 with a full scholarship… I like 18 to 22… I really like that age range.”

I made sure to ask about his parents and they are both alive and well, with his father turning 80 this year. His great grandmother, who had given him the set of 1950’s Encyclopedia Brittanica’s, passed during the 70’s while he was a senior in high school.

Aspirations: “The biggest message I want to get across to everybody is that one day, you need to pay it forward.”

There was a light knock on the door and his secretary popped her head into the room. “Your ten o’clock is here.” I was scrambling to get in some final questions:

Me: “For the Campus in general, what are your aspirations for the next five to six years?”

POTC: “The biggest one right now is… to build the third phase of North Village, to get more apartments on campus, and to dramatically renovate this [Decker Student Center] building. If not build a new campus center. I think those are two critical physical things that need to happen… What we’ve done in the Library… these are the standards, the aesthetic standards, we really need on campus… so really enhancing the aesthetics of where students ‘hang out,’ you know I want there to be more places where people hang out. And then, continuing the kind of scholarship support… I’m incredibly proud of that. Because I know I wouldn’t have gone to college if it hadn’t been for people helping me go to school, and I really feel an absolute need to pay that back. The biggest message I want to get across to everybody is that one day, you need to pay it forward.”

He put his coffee mug on the table in front of us and stood saying we needed to wrap up. I agreed and quickly shut my laptop, put it away, closed my sacred notebook with the miniscule amount of notes I’d taken on the interview and put it in my bag.

He waited patiently for me with the door open as I finished packing up, slung my messenger bag over my shoulder and quickly grabbed my phone, which was still recording, before I forgot it. I turned to him and thanked him for his time, shaking his hand firmly and then walked out as his next appointment walked past me.

Quotes adjusted for clarity.