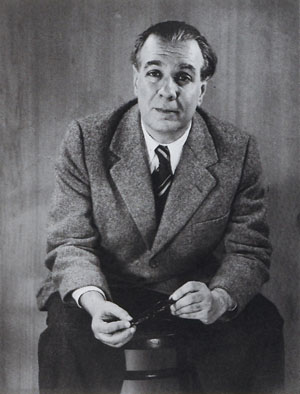

Never one to defy expectations, Jorge Luis Borges, in his 86 years, managed to become one of the most prolific authors of Latin American literature. His life began as humbly as most; born in a Buenos Aires suburb to Leonor Suarez and Jorge Haslam, Borges was raised in the Palermo region, then a poorer section of the city. At only nine years old, Borges’s interest in literature manifested when he translated The Happy Prince by Oscar Wilde into Spanish and had it published in a local newspaper. This inspiration likely stemmed from his father, who held dreams of publishing. However, Borges noted that his father “tried to become a writer and failed in the attempt.”

Borges’s interest in education and literature continued into his teen years. By 11, he was bilingual in English and Spanish, and by 12 he had developed a keen interest in Shakespeare. In 1914, when Borges was a mere 15 years old, his family moved to Geneva in Switzerland. While there, Borges learned even more languages: French for conversation and German for philosophy.

At the age of 18, Borges graduated from the College de Geneve (now known as College Calvin) and, with their oldest finished with school, the Borges family decided to wait out the remainder of the Great War in Switzerland. Borges’s criticism of communism during this period would color his writings for the remainder of his life.

Borges’s literary work expanded in volume, ranging from fiction to a pair of journals: Prisma and Proa, both based back in Buenos Aires. It was only in the mid-1930s, however, that Borges branched out from his former styles and began to study existential fiction. As with many Latin American writers of the time, he developed a style popularly known as Irreality, a structure that shares much in common with postmodernism.

1933 marked a drastic shift in Borges’s career; he moved to an editorial position of a branch of the Critica newspaper. It was here that he first published his collection of writings, famous as the Universal History of Infamy today. Again showing his postmodern and anti-authoritarian leanings, Borges’s pieces were written in two styles: one a collection of non-fiction essay and stories, and the other a set of forged documents passed off as translations of seldom-read essays.

Borges’s unique style of writing continued for a long while. He gained initial renown overseas from his poems translated to the “Collected Fictions” anthology as well as his acceptance of the first Prix International award. After a spike in interest, Borges went on several tours of the United States, lecturing to aspiring writers.

He published quickly and prolifically, often earning awards for the poetic and existential nature of his writings. Borges’s writings, immersed in themes of mazes, time, and sexuality, are fantastical works designed to manipulate the concept of narration. Critics often attribute Borges’s vast imagination and innovative literary symbols to his progressive blindness. By 55, Borges was completely blind, yet continued to write for many years. This unique style persisted and intensified until he stopped writing, shortly before his death at 86.

Borges passed away in June of 1986 in his Geneva home. Although he is considered a writer of the twentieth century, his work still has profound meaning and shines light on the modern and postmodern movements.